A New Love In A New Town

Poussin and Antonioni work out what's going on. Jeremy Irons talks to himself. A premonition of spring.

A few times, I’ve experienced something like Stendhal Syndrome, an overwhelmingly intense reaction, or overreaction, to a work of art. Among the infinitely replicable patterns of the tiles in the Topkapi Palace in Istanbul, I lost my limits in a strange vertigo. And the opening scene of Michelangelo Antonioni’s film L’Eclisse (The Eclipse) seems always to induce a heightened state, a surplus of response that’s almost delirious. I think it’s something to do with the way visual energy runs around circuits of form without escaping, an artwork like a kind of perpetual motion machine. In part it’s that, the containment; in the Antonioni it’s also the density of composition, every brief shot a perfectly finished thought, framed, changing, gradually revealing the space we’re in, the relationship between the characters. It’s so much; that one scene would make a tremendous photobook in itself.

Antonioni made a trilogy of films from 1960 to 1962 that I love, L’Avventura, La Notte, and L’Eclisse. They are rich, ruminative, stylish, complex, witty, weird, despairing, stoical. I return to them because they contain so much, and because they are supremely visual. When I watch a film I want primarily to see. Antonioni looks at the world as well as anyone ever. There’s a very good book about him by the classicist and critic William Arrowsmith, Antonioni: The Poet Of Images, published posthumously in 1995. He makes big claims for the director: ‘Antonioni is one of the greatest living artists, and as a director of film, his only living peer is Kurosawa; and he is unmistakably the peer of the other great masters in all the arts. As an innovator and manipulator of images, he is the peer of Joyce in the novel; in creating a genuine cinematic poetry, he stands on a level with Valéry and Eliot in poetry proper; and that his artistic vision, while perhaps no greater than that of Fitzgerald or Eliot or Montale or Pavese, is at least as great and compelling,’ and I think he may well be right. Certainly, there’s a thoght-through and supple, unified method in that trilogy that feels almost like a new language, certainly a new combination.

Oh, and the suits. I lament the passing of the suits. And cigarettes.

This is all by way of an introduction to a piece of writing about a painting and one of these films, La Notte, which probably serves best as an introduction to the film, a long letter of recommendation. There’s a lot more in the film than I describe. I’m really just happy to have a reason to post a lot of stills.

Just before that, I’ve discovered that I can insert a ‘share’ button like this:

Do please share Odradek’s Joy with anyone you think might like it.

Two In The Campagna: Poussin and Antonioni

The air is dry and clear. Sunlight falls through it, revealing everything with a hard lucidity. Revealing what? A landscape with two female figures in the foreground; one is on her knees scrabbling at the earth or rather at a shapeless grey mass on the earth, the other is upright, apparently in a state of anxious vigilance. She twists around to see something, the fingers of one hand tensely outspread. Perhaps she has heard a noise. Perhaps its source was that man reclining in the shadows under the group of trees on the right. The turning figure’s arrested motion marks the image’s duration, its shutter speed: an instant. The foreground figures are in a kind of crisis. They are beside a road that leads behind them between two groups of trees and back through a low wall that marks, it seems, the perimeter of a town. Within the wall is a kind of park or maidan area with figures in various small groups. The town rises in the distance, at the centre of the view an elegant temple built on higher ground. Behind the various kinds of buildings are trees and rising above it all a rock formation, massive and bare beneath a complex cloud formation. In the foreground, panic, a frantic moment; in the background, the stasis of rock, the indifferent motions of clouds. Between them, a town.

‘Towns are the illusion that things hang together somehow,’ writes the poet Anne Carson. The boundary makes the whole, defines the together. In Poussin’s painting, the two foreground figures are conspicuously beyond a boundary. What hangs together where they aren’t? The town seems at leisure. Within its limits, there are figures reading, playing the flute, practising archery, swimming. They relax in that elegant recumbent Hellenic posture – of feasting, of the symposium – the posture that Jews imitate during the Passover meal as a physical statement of their freedom. Someone draws water from a well. Someone grooms a horse. People walk between the grand columns of the temple. Outside the town, a woman struggles to collect ashes with her bare hands while her companion keeps watch. The ashes are all that remains of her husband, Phocion, an honest politician executed for treason (the accusation was false) and cremated beyond the city walls. In collecting these remains she defies the law, hence her companions pirouette of panic at the thought of being seen.

The clear sunlight shines equally on all of this, all framed by Poussin’s view, set back and seeing far with a crystalline depth of field. The painting’s town holds together for inspection the apparently serene community and the people, the death, the awkward truth it excludes. Equality of attention and scrupulous technique is essential to the power of this vision. The drama of grief and exile is lit by the same light that falls on the background figures, the buildings, the stones and grass and water, on the different cloud formations. Poussin takes tremendous care with the way light hits each individual uppermost leaf on one side of a tree, leaving those below in shadow. It is here, in the apparently innumerable specified leaves, that I see Poussin’s almost superhuman patience, his determination to reveal a truth of the world, of the human condition, by seeing everything through to the end. Poussin’s town is that of contradiction: inside and outside, order and hypocrisy, pleasure and suffering. He shows us what the community he depicts refuses to see.

Power of any kind, because it is violence, never looks: if it looked one minute longer (one minute too much) it would lose its essence as power. The artist, for his part, stops and looks lengthily … This is dangerous, because to look longer than expected … disturbs established orders of every kind, to the extent that normally the length of the look is controlled by society; hence the scandalous nature of certain photographs and certain films, not the most indecent or the most combative, but just the most ‘poised.’

This is Roland Barthes in his homage to the filmmaker Michelangelo Antonioni, ‘Cher Antonioni.’ Certainly, Poussin looks lengthily with an interrogative gaze, his painting a repeated answering of the question What does this look like? How are a loved one’s ashes gathered in haste? How is a horse groomed, an arrow loosed, a flute played? How do people ignore injustice and death? Whether this is truly a dangerous activity in Barthes’ terms depends on whether we understand him to refer to a danger to the established order of one’s preconceptions or to the actual social order. The transition from the aesthetic to the political in cultural criticism is often a moment of wishfulness or utopianism when the effect of art on imaginary other people is fantasised. In satire or agitprop, the intended effect is obvious: a disgust that helps motivate action. In Poussin’s painting, the world is offered for scrutiny and meditation. He shows us the strangeness of the simultaneity of different kinds of experience. I’m always struck by the placement of potted plants between the columns of a sort of veranda of a building (perhaps it’s an orangery) on the right of the painting, set far behind the anguish in the foreground. That decorative domestic care, the pleasing precision, contrasts so cruelly with the pain over the burnt remains of a man. They exist together as a kind of equation, the two terms of Walter Benjamin’s famous dictum that every document of civilisation is a document of barbarism. Revealing this, I suppose, disturbs civilisation’s established order at least in the mind of the viewer. There was a revival of interest in Stoic literature among Poussin’s circle. The fate of Phocion is a fitting subject for Stoic contemplation, the perennial nature of injustice that must be endured. The lucidity of Poussin’s technique here makes this inescapably visible.

Poussin’s paintings think through, they organise, they study. His work embodies ‘high fictions’ as Hazlitt wrote of him, his pictures ‘denote a foregone conclusion.’ But sheer materiality always finally escapes the coercion of an idea. He is not an artist of the pathetic fallacy; his worlds do not sympathise with or extrapolate from his figures. No rain falls because they are sad. Rather, his figures bear the burden of humanity, their subjectivity in an objective world of unrelated facts.

Poussin cast his figures, selected them in a way that a film director might, from the range of types and poses offered by the classical sculpture he studied and drew. Roman friends and patrons collected classical sculptures and made them available for inspection as well as commissioning artists, including Poussin, to depict them. He found ideals of embodiment that could then be brought together in complex combinations. He is also known to have worked at times with a box in which he placed figures he’d modelled from wax. He pressed wet cloth to these figures to simulate falling drapery. Apertures in the side of the box allowed him to control the direction and angle of light. Poussin looked through an aperture at the end that presented the viewer’s single viewpoint. He looked long and hard at these boxed scenes, making ink and wash drawings for them to establish the action of light over the figurines in his exemplary dramas.

The legacy of classical models can be seen in Poussin’s painting of hands. He is one of the great artists of hands and differs from the others in laying hands bare in their essential human capacity, their generalist, unlimited possibilities, uncaptured by any particular task or emotional connotation. Caravaggio’s most memorable hands, with dirt under their fingernails, speak of violence and labour and the convergence of those things in poverty. Watteau’s hands are subtle, caressive, articulate. They are the guitar-playing, letter-writing, fan-fluttering, delicate hands of loverhood. Schiele’s hands with their long spatulate fingers, often upraised, often with two fingers twined together, are intellectual, burdened with an anxious sensitivity that makes their grip on the world seem likely to be either too strong or too weak.

The hands in Poussin’s paintings are seen in a great number of positions and tasks. When they attract most attention, they are often empty, either pointing or, as in the case of the attendant in Landscape With The Ashes of Phocion, gesticulating with outspread fingers. He is precise with the fall of light and shadows along the planes of fingers and sculpts their three dimensions. This makes vivid the empty space between them. In the moment of crisis, the hand can grasp nothing, its limitless versatility, is unavailing, isolated in an indifferent world.

Landscape With The Ashes of Phocion is a study in indifference, (at best indifference). Other hands within the city walls groom a horse, cover the stops of a flute, cast a net, draw back the string of a bow. Outside, the widow’s hands scrape together the ashes of her husband.

There is a figure very like Phocion in Antioni’s film La Notte. He too is virtuous, serious, uncompromising, and his death is both central and peripheral, existing beyond the boundary of the social world in which the film mostly dwells. Antonioni is an artist very like Poussin. He too has the clear, patient, interrogative gaze, watching how things hang together and where the edges are. He makes careful, exquisite formal arrangements; the contents of his films are in Barthes’ word ‘poised.’ Like Poussin’s paint, his camera investigates the plain material being of the world, its solidities and vacancies at the same time as the overlaid configurations of society and its values.

La Notte begins by announcing its preoccupation with modernity, the strangeness of the historical present in which it was made. A shot of a busy Milanese street shows a van delivering televisions and other electronics as yet, in 1961, to permeate every Italian household. The camera then sweeps up into the sky and begins a slow descent of a tall modern building, the cityscape reflected in its glass façade. The soundtrack is of electronic music, beeps and buzzes that sound like active communications. The camera then passes through the glass and enters the hospital room where the film’s Phocion, the intellectual Tommaso Garani, is dying. He is visited by his friends, an attractive couple – superlatively, cinematically attractive – the fashionable novelist Giovanni Pontano and his wife Lidia, played by Marcello Mastroianni and Jeanne Moreau. Their conversation quickly establishes Tommaso’s moral seriousness: Giovanni praises an article he has written about Theodor Adorno. Tommaso is dismissive. He compliments Giovanni on the publication of his new novel, copies of which we later see at its launch party. It bears the beguilingly suggestive title La Stagione, The Season, a title that accords with the film’s interest in ephemerality and change. Perhaps Giovanni fears his popular success will prove ephemeral; certainly, he seems to display an author’s diffidence about his own work in the face of Tommaso’s praise. But here, as often throughout La Notte, Giovanni is hard to read. He is laconic, his affect limited. His opacity is clearly a source of tension in his marriage with Lidia, the decay of which is arguably the film’s central concern. This self-involved blankness sometimes make the film seem like Fellini’s 8½ turned inside out. In Fellini’s film, Mastroianni plays a film director often surrounded by the phantasmagoria of his inner life – his memories, fantasies, the actors he has cast, the sets he has had built. In La Notte Mastroianni is isolated and contained like a figure in a Poussin painting. His inner life hidden from view, his art a silent object commodified for sale, piled in a shop window. (Later the question will be if more of him is for sale when he is offered a highly paid job in corporate communications).

Tommaso Garani is in apparently no danger of being similarly co-opted and absorbed into the capitalist machine. His interest in Adorno marks him as precognizant. Besides, an intellectual of the small serious journals lacks the commercial possibilities of a popular novelist. Moreover, like Phocion, he will soon be ultimately excluded: he will be dead. He makes this exact point in the dialogue, telling Giovanni “The advantage of a premature death: you escape success.”

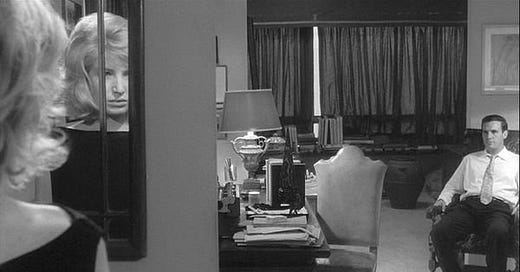

In the hospital room, Lidia cannot bear the sight of Tommaso’s suffering. She is overwhelmed by it and excuses herself. We follow her outside where Antonioni shows her against the massive flat geometry of the building, sometimes tiny in a longshot, images of the smallness of a human being in an unyielding world. We watch her lean against a wall and cry. Throughout the film, Lidia’s suffering is overt. She is the opposite of Giovanni: open, sensitive, expressive, fretted with pain. Jeanne Moreau’s wide eyes with soft half-circles of shadow beneath them, her sensual mouth hardening with disappointment and things unsaid, her small stature, her small burdened shoulders, all constantly play out her changing emotional state. She is the ideal contrast to the other central woman in the film, Valentina Gherardini, played by Monica Vitti. Valentina is the daughter of the industrialist who offers Giovanni a job. Before he knows her identity, Giovanni, intent on an adulterous liaison, starts pursuing her, crudely, carelessly within sight of Lidia. While Lidia looks like the forsaken, Valentina looks like the desired. She is tall, her face all angles, aquiline, with high cheekbones and long, narrow eyes. She looks expensive, chic, as though designed in the same way as a piece of haute couture. Giovanni’s pursuit of her reads not only as the desire of a selfish man in a failing marriage but, as we would say now, aspirational. He waylays her in several futile conversations but fails to achieve the outcome he wants. It is Lidia, in fact, who forms a deeper relationship with Valentina, a brief sisterly solidarity founded on their shared annoyance at Giovanni.

Giovanni is trying to break away, to find something new. Lidia is trying to keep what she, what they, already have, knowing perhaps that it is already too broken and that she is too late. From the hospital they drive to Giovanni’s book launch where he is besieged by the effect of his success, a press of people asking him banal questions and the snapping of cameras. His sombre, pensive, standardised authorial face appears in photographs on the backs of the books and on a poster. Lidia is sidelined here and while Giovanni is surrounded she slips away into the street. She walks. She observes. She becomes the film’s gaze, or rather concentrates the viewer’s gaze, as she scrutinises the city’s people and hard surfaces. She asks what kind of town is this? What hangs together here?

And what hangs together in her? Sooner or later the viewer notices her dress and the leaf pattern of its fabric and realises at some level her affiliation with life and growth, and the contrast that makes with the city. She slips along its channels almost like a lost utopia. If only Giovanni could see her the way the film does, could live up to her honesty and fidelity. If only all the Giovannis could, what a difference there would be. She hears a child crying and finds it, a half-dressed infant which she stops to comfort. She walks on, out of the centre of town.

In an open grassy expanse, some young men are setting off large rockets. Lidia lingers among the gathered crowd to watch. The rockets are loud. They fizz and scream and corkscrew violently up into the sky. At the time of the film’s release they may well have trailed connotations of the Cold War, then its most dangerous moment of nuclear brinksmanship, or of the space race. For me, the rockets surging upward release reminds me of a detail in Poussin’s painting.

The rock formation stands in the centre of the painting, its irregular monochromatic form like a natural piece of abstract sculpture. Near its centre is a hole, a gap, a tunnel, a space of visible sky. Once I had noticed it, my eye kept returning, keeps returning to this that shape of blue. It felt like relief from the painting’s relentless pursuit of hard facts, a kind of valve releasing pressure. The rockets release energy too, up into the empty sky. They are an escape, but like the opening through the rock, they only go so far. They are neither transcendent nor transformative. They are the idea of escape and mark an outer limit, a zenith of possibility.

Lidia moves on. Her walk takes her back to a small slightly down at heel area where a radio plays mindlessly cheerful pop music at a refreshment stand and a few people lounge at outdoor tables. From here she calls Giovanni who, after briefly looking for her, had fallen asleep in their apartment. He knows the area, too; it’s an old haunt of theirs, from the early days of their relationship. He joins her there and comments on the disused rails of the train or tram that used to run when they frequented the place. Grass and tall weeds cover them now. The symbolism is heavy. Both seem to see it and regret it. They are tender and calm with each other. Giovanni tries to claim things are as they were:

Giovanni: It’s hardly changed.

Lidia: It will soon.

Limits. Endings. The change of seasons. La Notte is the middle film of a trilogy, following L’Aventura and preceding L’Eclisse. Narratively unrelated to each other, they share their immaculate black and white cinematography, scrupulous composition, their melancholy and passionate restraint, a preoccupation with change and breakdown, an old world dying and a new one not yet born. Taken together they an extraordinarily rich and complex whole and make, I think, the strongest case for William Arrowsmith’s claim that Antonioni is a revolutionary, language-extending artist on a par with Picasso and Stravinsky. The three films scrutinise their people and environments as if they might finally see this new thing emerge, might fully comprehend what hangs together. Meanwhile, Giovanni and Lidia walk together among insufficiencies of the old and new. Their failing marriage is symptomatic, albeit an old story – love fading, empty repetition, faithlessness, loneliness, with its roots in nineteenth century fiction’s investigations of the bourgeois marriage. Here again, the marriage is an instantiation of a society unsure of its desires and possibilities, and a lens through which to view them.

Herman Broch’s novel The Sleepwalkers, written in the 1930s, is another work of fiction preoccupied with the anxious predicament of the failure of society’s values and the vertigo of the groundlessness before new ones are established. It is set in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the period Broch referred to as ‘the gay apocalypse.’ It comes as a surprise to Giovanni to find a copy of The Sleepwalkers lying around when he and Lidia arrive at a grand party at the villa of the industrialist Gherardini and the night of La Notte properly begins. “Who here would be reading The Sleepwalkers?” he asks. It will come as less of a surprise to the viewer, should they know the novel. The novel will be revealed to belong to Valentina, a fact that seems to make Giovanni desire her more, as if she may know some answers or at least be in intellectual sympathy with him.

The party seems like a typical evening in a gay apocalypse, a festive florid abundance of morbid symptoms. Its first appearance is of strange spectacle. Lidia and Giovanni pass through the house and out into the garden where a crowd in smart evening wear surround a man on a glossy, restive racehorse. Gherardini owns this horse. A recent win is being celebrated. The horse steps nervously in the middle of the throng of loud, slightly drunken people; a complex image with which Antonioni seems to want to surprise us, framed first at a distance, before the camera pulls in. The phantasmagoria of wealth and luxury, the magnate’s power of subordination and the unruly energy that resists this, all in view as the horse shakes its head and the crowd raise a toast. Someone familiar with Poussin’s works might think at this moment of his painting of the Adoration of the Golden Calf, another image of a similar circle of humans around an animal. The party seems prone to outbreaks of regressive pagan classicism: later a rainstorm causes an outbreak of uproarious behaviour, including clothed people throwing themselves into the swimming pool. There is an outside dance floor with a statue of Pan at its centre. Under the drenching rain it looks sleek and slippery. The final dancer, a woman in a state of wild arousal, kisses and caresses the statue. The villa itself is redolent of ancient Italy, a new, modernist example of the old tradition of successful Etruscans, Romans, Italians, declaring their status with large, imposing homes on the edge of the city. It is in one of the many rooms in this home that Gherardini offers Giovanni a job, a chance to forsake artistic values for wealth and position.

The party contains ecstasies, depressions, courteous small talk, old friendships, business deals, abundant food, flowers, music, swimming, dancing, games, infidelities. Giovanni pursues Valentina. An unnamed man pursues Lidia. In the middle of it all, Lidia absents herself to use the telephone and calls the hospital. She learns that Tommaso Garani has just died. His death has occurred out of sight, beyond the boundary of party town. She breaks the news to Giovanni much later when they are leaving the party. It is pale dawn. They walk together away from the villa and into the surrounding countryside in their now incongruous evening clothes. They sit down and discuss their failing marriage, Giovanni’s failure’s in particular. Lidia reads from a beautiful and intensely passionate love letter that Giovanni does not even remember having written years ago. When Lidia seems to pronounce their relationship dead, Giovanni lunges at her and grapples her into an embrace. She complains but he won’t let go. Refusing to accept their season is over, he kisses her neck while she insists, “I don’t love you any more. You don’t love me either.” They writhe together in a little hollow of sand. This little hollow turns out to be a bunker. The gently rolling Italian landscape into which they have walked has been turned into a golf course. The day is new and strange.

Youtube Treasure #5

A beautiful short late Beckett play, a great poem of grief, delivered with passionate understatement by Jeremy Irons. His performance, the quiet, unemphatic voice, the detailed thought going on, couldn’t be better.

Weather Diary

February 2nd

2 degrees. Smooth, wide clouds, dove grey. In the evening, a new violence. The temperature dropping, trees surging in the wind. The day roughly handled, hurried into night.

February 3rd

-18 degrees. Air stings the lungs, a piercing emptiness. Houses issue bright steam from their outflow pipes. Car exhaust turns to vapour. The wind hurts; it rattles the trees. The sun floods everything with light but no heat, a distant radiation. Canadian teenagers don’t care though, walking to school in sweatpants and light jackets, heads bare, talking, interested only in each other.

February 4th

-14 degrees, rising to -2. The polar hallucination withdraws behind a screen of cloud that drops gentle snow. A, enchanting Victorian Christmas instead that lasts most of the day.

February 5th

5 degrees. The warmth loosens the snow which falls from high places. When a large load gives way and slides from the roof there’s a noise and a shudder through the house like a heavy lorry is going past. Sometimes you glimpse it happening, catch it in the act, mid-air, a white shape hurrying past.

February 6th

-2. Scars of ice closing on yesterday’s melt. And opening again in the sun. In the afternoon the sky clears, washed through with a pale sunlight. A quiet afternoon; muted, convalescent.

February 7th

7 degrees. Wet and heavy. Snow banks leaking. General loosening and sinking of dark water. In the afternoon, games afternoon weather. The stolid ground and flat white light of a rugby match.

February 8th

7 degrees. Sunlight. Gentleness. A prevision of spring. Birds sparking about. Scarlet flame of a cardinal quick through an empty hedge, flying up into a tree, zapping its voice.

February 9th

3 degrees. Yesterday’s mood, evidently unstable, is gone. Dark, heavy rain, erasing the old snow. Hours and hours. Tragic, long-haired rain, inconsolable, weeping down the windows.