Boom

As a fan of Kipling I was pleased to find myself in excellent company the other day when I came across this reminiscence of Borges in an interview with Alberto Manguel:

Alberto Manguel: He [Borges] wasn’t interested in food, as he wasn’t interested in music or visual arts. He was only interested in the word and the shared word and where the word could take you. It’s mental maps—going back to the idea of maps—that literature unscrolls for us. And during the meals, he didn’t want to be distracted by the food, whether good or bad. It had to be bland. I remember the scandal he caused at Harvard when he was giving those marvelous lectures on poetry.

PH: The Norton Lectures.

AM: Yes, it’s called the Craft of Verse, one of his best books. They invited him to a grand dinner and they asked him what he wanted to eat. He asked for Campbell’s tomato soup.

PH: How fantastic.

AM: He caused a scandal among the university gourmets.

PH: That is a magnificent story.

I’m sure you’ve been asked this question many times, but what did you take most pleasure in reading to him? Or differently put, what did he love for you to read most?

AM: The situation in which I found myself was peculiar because I was 15 or 16 and at the time I was working at a bookstore in Buenos Aires where Borges came to buy his books. He asked me one day whether I wanted to come in the evenings to read to him. I thought it was just a favor that I was doing for this nice, old blind man—little did I know what gift fortune was laying in my path.

But it wasn’t a reading as we would say if you asked me to come and read for you and I choose something and I would read it out to you in my intonation. He had a plan.

When he became blind in the mid 50s, he decided that he would no longer write prose. He would write poetry because he said that poetry came to him as music, to which he added words and then he could dictate those words. But that to write prose, he said, he had to see his hand write. So he had stopped writing prose, but over the years the arguments and plots and ideas for stories came to him.

After a time—this is in the mid 60s, so 10 years into his blindness—he wanted to revisit the stories that he thought were great. Borges had very peculiar taste. He thought of certain writers as “the great writers.” The best writer of French, for him, was Voltaire. The best writer in Portuguese was Eça de Queiroz. The best writers in English were Stevenson, Kipling, Chesterton, and Sir Thomas Browne.

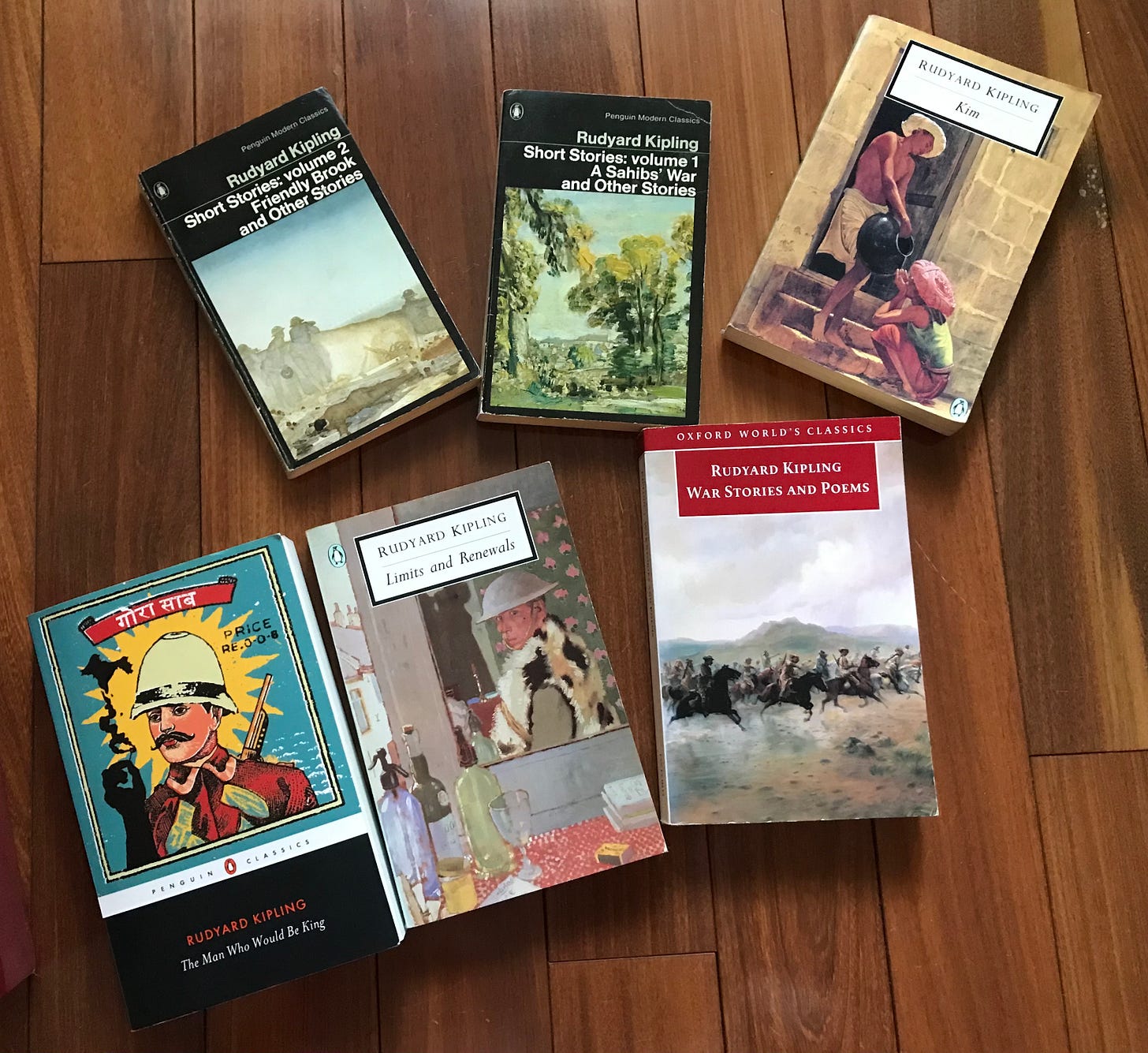

Looking for stories, he would ask me to read to him Kipling, Henry James, Stevenson, Chesterton, but above all Kipling. Few people read Kipling nowadays. They have this idea that either he is this Imperialist and therefore should not be read; or a writer of stories for children and they think of The Jungle Book. But Kipling is so much more. His early stories and his very complex, dark later stories are absolute masterpieces. And I discovered them thanks to Borges. If I had to thank Borges for just one thing, it would be for the discovery of Kipling.

PH: What Kipling?

AM: Well the stories from Plain Tales from the Hills for instance. Borges calls them a laconic masterpiece, and that they are. And the later stories: “The Wish House” or “Mary Postgate” or “Unprofessional.” These are stories that we don’t read now, but if somebody wants to learn to write in English I would say first read Kipling.

PH: How extraordinary. I don’t know these stories.

AM: You have a wonderful time in front of you.

Here’s a moment of that wonderful time, the opening paragraph of Kipling’s short story They (I’ve linked to it online but I suggest finding it on a page. It really deserves the presence of physical form and the wide formatting of this online text somehow spreads the impact of the sentences which should be closer to each other and closer to you. If the rich, strange world of this story feels familiar as you read, it might be because the disappearing children, their audible laughter, are taken up by T.S. Eliot in the first of the Four Quartets):

‘ONE view called me to another; one hill top to its fellow, half across the county, and since I could answer at no more trouble than the snapping forward of a lever, I let the county flow under my wheels. The orchid-studded flats of the East gave way to the thyme, ilex, and grey grass of the Downs; these again to the rich cornland and fig-trees of the lower coast, where you carry the beat of the tide on your left hand for fifteen level miles; and when at last I turned inland through a huddle of rounded hills and woods I had run myself clean out of my known marks. Beyond that precise hamlet which stands godmother to the capital of the United States, I found hidden villages where bees, the only things awake, boomed in eighty-foot lindens that overhung grey Norman churches; miraculous brooks diving under stone bridges built for heavier traffic than would ever vex them again; tithe-barns larger than their churches, and an old smithy that cried out aloud how it had once been a hall of the Knights of the Temple. Gipsies I found on a common where the gorse, bracken, and heath fought it out together up a mile of Roman road; and a little further on I disturbed a red fox rolling dog-fashion in the naked sunlight.’

This seems to me, more and more, ideal prose, ecstatic but expedient, as purposeful as it is sensuous. The tactile compression in Kipling’s verbs is often brilliant - here the county flowing under the wheels of the car, the sea beating on your left hand: not your left hand side but your left hand, against your skin. Later in the story, the blind woman and our narrator are by the fireside:

‘“…Please do something to that fire. They won’t let me play with it, but I can feel it’s behaving badly. Hit it!”

I looked on either side of the deep fireplace, and found but a half-charred hedge-stake with which I punched a black log into flame.’

‘Punched’ into flame!

Notice also the judicious achievement of this moment: ‘I found hidden villages where bees, the only things awake, boomed in eighty-foot lindens that overhung grey Norman churches.’ The subclause is so important here; without it we have ‘I found hidden villages where bees boomed in eighty-foot lindens’ which is heavy-handedly alliterative and absurd. The brief delay allows ‘bees’ and ‘boomed’ to coexist. More than that, it makes the sound of the bees really register for the reader. ‘Boomed’ is such a vivid surprise. The subclause creates a pause in which the reader must wait for the answer to the question of what the bees, the only things awake, did: flew? buzzed? patrolled? searched for flowers? No, they boomed, and you hear it, that heavy throb of sound when they pass close to your ear.

Great writing does many things - this complicated and mysterious short story does a lot of them - but I’m a simpleton: the feel of the sea, the sound of the bees in the lindens is pretty much all I need.

Normal And Strange

And from there I was to go on into my discussion of Tender Is The Night and after announce a hiatus while I finish a novel and move house. But this strange week produced some postponement. I’ll get back to Tender Is The Night soon.

The air has been - still is - sour-smelling, heavy with the particulate matter that is the afterlife of burned forests. Though less densely polluted than it has been in New York, Toronto has also had a sepia cast, a coppery light at the edge of things. On cloudy days it has been very dark and when it rained, a shifting darkness within darkness. I had to go out several times and arrived home with a scraped throat and that hard flat feeling in my lungs familiar to social smokers after a night out. (I have known worse, or at least as bad, in India and China. Shanghai broke me years ago; I’ve been mildly asthmatic since). The rest of the time, I’ve been indoors with aching sinuses. You can picture me, trying to write, looking out of the closed windows at the view tinged a weird colour with pulverised life on a heating planet. What pervades is an unease, a physical unease, that can be driven out of awareness with concerted concentration on something concentration but that does not ever depart. It is not an unfamiliar sensation. I’ve smelt burning forests and seen the light dimmed in Toronto before. Moreover, I’ve felt something all my life. I remember a similar unease growing up on the edge of London from the light pollution at night, the endless orange haze, clouds turned bruise-brown: evidence that there was too much of our human life, that its effects were altering and unlimited. I knew it from the passion I felt for bright living things as a young bird watcher, interested in natural history. I felt E. O. Wilson’s ‘biophilia.’

What strikes me now is how clearly as a child I had the sense that things ought to be otherwise, that they had been, that there was an original kind of human life that we weren’t living. I knew it from the passion I felt for bright living things as a young bird watcher, interested in natural history. I felt E. O. Wilson’s ‘biophilia.’ Later I read the theory and believe it. Our sense of health, of the viability of our life, connects with the vitality of life around us. We are delighted by its variety, by its complexity. (I think some people experience a cognate pleasure in orchestral music: the many different instruments fitting together, the radiant whole, the unfolding process).

A year or so ago I got interested in human evolution and prehistory, reading books by Chris Stringer and Ian Tattersall, and Bruno David’s brilliant book on cave art. It’s a fascinating subject, and one that is developing surprisingly quickly at the moment, with new insights into Neanderthal culture happening all the time, and the relatively recent discoveries of home floriensis and homo naledi. Our own homo sapiens prehistory is of course vastly longer than our recorded history, hundreds of thousands of years of continuous human life have preceded the last couple of thousand and their quick convulsion of history and technology.

The imagination leans in, as far as it can, to those great stretches of time of continuity and survival, as though there’s something it might find there, might understand. I come across this in a notebook I was keeping at the time: ‘Few of them, scattered, beadmakers, exchanging words, singing in the vast night, firelit. Killing and eating. Giving birth. Sheltering. Surviving, surviving. Leaving footprints. Dropping white bones in the landscape. Dressing bodies with beads and ochre, setting them down.’

But this is nothing, an image, a dream. It is part of the uneasy feeling while the light is dim.

I very much like this entry. Kipling is absolutely immersive, and it is good to be reminded of his art. As for Borges, along with Pablo Neruda, he is one of the geniuses about which I feel least friendly. Marvelous art and a terribly questionable human being. He was all to Anglophile and cozy with fascists for my liking. I dare say that comes out in some of his works, particularly the short stories. Finally, meditating on early mankind is one of my favorite occupations. More recently, I have become fascinated by the advanced civilization of Mesopotamia, which had its whole cosmology and brilliance for 3000 years prior to the Judeo Christian era. Babylon! Now there’s a place in the past I would love to visit! Warm regards, maestro.