The Only Story

There is only one story and we all know what it is. Alec Soth looks at pictures. The green leaves at night. Bright steam and plummeting temperatures.

I was planning to write about Yiyun Li, Claire-Louise-Bennett, Ariana Harwicz and others, about dignified and explosive writing, but was blown off course a bit this week. I’ll come back to all that next time. Meanwhile, we may as well get this out of the way and acknowledge that Odradek’s Joy is now only experienced within ambient conditions of anxiety, within decaying certainties, with the future faltering.

In recent years I’ve noticed that climate fear diminishes during the winters and returns ever stronger with the floods and fires of summer. We’re getting quite used to a new set of images on the TV news: huge forests burning, tourists taking refuge in the sea while the resort goes up in flames, phone footage of cars speeding through tunnels of fire, the drivers whimpering; cars, buses, bits of houses floating down streets of mud-brown water, people canoeing through the neighbourhood or sitting on their roofs, the elderly being helped into boats. This will soon be back on our screens and in our lives. Last year here in Toronto, forest fires gave the air a sweet, oddly pleasant cigar smoke smell and made the moon glow bright orange.

There have been plenty of reasons for anxiety in the past before but this one is obviously different. It’s a drama where the main conflict is the scenery burning down around the actors. It is the death of repetition, of the cyclical. There is no simple cessation and rebuilding to be done, as after the destruction of a war. There is no world to be had outside of the human situation: our stuff is everywhere, in everything. There is no clear narrative of personal responsibility or cause and effect: causes and effects are now out of our hands, running out of control.

I think this is all very hard to write about in fiction because this content goes vertical: it stands up out of the story, projecting in to our immediate understanding of what is urgent and not being attended to - not being attended to while we read the book, certainly. And it baffles our usual narrative sense of agency. And there is that lingering demand for the redemptive, for hope of some kind, which so easily strikes a false not of willed assertion of the brave human spirit and all that.

In the piece below, I try to order some of this experience by thinking through my experience of a particular painting, one that puts the ordinary pleasure of life, and the anxiety, the new modern conditions, all together. Years ago I was asked to give a position paper at a conference of historians discussing World War One counterfactuals (oddly enough). My paper was about where the arts might have gone without the the First World War. My provocation was that things would have ended up in much the same place because modernity was already well begun (Cubism, atonal music etc) and another technological war would have taken place. And the background conditions were already ratcheting up. I illustrated that argument with this painting.

Bathers At Asnières

This painting splits the world in two. It does it every time.

The National Gallery in London is my favourite place, the centre of the city. I go often and have done since I was a teenager. Each time I enter, coming in out of the wide, unpredictable restless space of Trafalgar Square, I feel that blended sense of calm, familiarity, relief, and quiet purpose that is coming home. I like to have its ceilings over my head. Even working in its shops for a couple of years did not change this reaction. The fact that it is free still amazes me, that you can walk in off the street, speak to no one, pay no money, and a minute later hold eye contact with a Rembrandt self portrait or be present at Piero della Francesca’s Baptism of Christ. The gallery defies the monetising city, like public libraries and churches, and enlarges unquantifiably the available conceptual space.

The National Gallery’s ground plan of long successions of rooms separated by glass-panelled inner doors means that there are vistas inside the building at the ends of which particular paintings are seen. These paintings, more insistently present than the others, seen often as you walk around, form part of the visitor’s mental map of the gallery, acting as points of orientation as you rise or sink through the centuries towards Florence or Venice or Paris or Provence. Frequent visitors, as a result, will be familiar with a view end-stopped by Stubb’s rearing horse Whistlejacket or the Renaissance gentleman and gathered possessions of Holbein’s The Ambassadors, or this large, luminous painting of 1884, Georges Seurat’s Bathers At Asnières. Sight of it indicates that you are heading towards the most modern part of the collection and the high fresh colour, the outdoor summer of Impression. These are the rooms that attract most visitors. They throng around Van Gogh’s sunflowers, Degas’s dancers and Monet’s glowing pond. At first sight, this Seurat seems to offer the same kind of recreation, a holiday for the senses; the sunlit riverside scene speaks directly to the body, inviting it to relax and inhale. Indeed, it is an image of leisure – as so much French painting of this period is – but it doesn’t take long to notice that the mood of the painting is oddly sombre. There is a heavy stillness to the separate figures. They seem at a loss. Longer inspection suggests that the painting’s immediate offer of pleasure is perhaps the same one made to the figures within it and that, for reasons that become clear, it is impossible to accept without discomfort. Bathers At Asnières is, it turns out, remarkably eloquent about a modern world, the one in which we live, where pleasure cannot be separated from anxiety.

I know this now so well, feel the discomfiting pertinence of this image so immediately, that it makes the walls of the gallery fall away. It makes me feel unhoused, exposed to the weather of my own present anxieties. I suppose this reveals in turn how much the pleasure of being in the National Gallery derives from the sensation of being sealed in a historical world, lustrous in its beauty and calm, complete, safely passed. The strange costumes worn in the paintings, outdated by several centuries, the ruffs, buckled shoes, swords and helmets, doge’s hats, the wigs and wide dresses of heavy silks, all intimate that this world is gone and that one may here enjoy the riches of a cultural inheritance that survives as that harmless stuff we call heritage. A place to marvel, to let the imagination roam among the mythologies, the religious mysteries and the expensive stuffs. Of course it does not take much actual historical analysis to dispel this phantasmagoric pleasure: long ago, John Berger taught us all how to connect oil painting with bourgeois property values and systems of oppression. But that is the kind of relevance that needs effort to be adduced and which curators’ labels strain to convey. Seurat’s Bathers, though, is so immediately part of the world as I know it that it leaves me nowhere to hide. I am disillusioned.

The sources of pleasure are obvious. Sun, water, rest. The source of anxiety takes longer to locate. No answer is immediately found among the figures who, solid, separate, mute, are alone in their thoughts. I can never decide whether the boy in the water wearing a re hat with his cupped hands raised to his mouth is warming his fingers by blowing on them or calling to someone we cannot see; either way, he is isolated. All the foreground and middle ground figures are averted from the viewer, either in profile or, like the boy in the water whose white, hunched shoulders confront us, facing away. Most are looking from the left side of the painting into the invisible distance beyond its right edge. Even the little dog belonging to the reclining man is turning around to do this. Further out on the water, in the distance, half of a scull can be seen, its oarsman bent forwards about to pull himself beyond the right edge of the painting with the next strike. To the left of him there are white sailed dinghies and one rowing boat containing three figures: a bourgeois couple, seated, the lady hidden behind the white circle of her parasol, the gentleman top-hatted, and a presumably hired boatman standing and rowing. From the front of the boat hangs a Tricolour. They seem to belong to a different, wealthier world to the figures in the foreground and indeed it seems that Seurat added them to the painting later to make a connection with the world of the Grande Jatte, his great painting of social types in their self-conscious display, which takes place on the green bank visible just beyond the little boat. The figures in the Grande Jatte are stiffly poised, erect, their silhouettes stylised and extended with bustles and hats, parasols and canes. The figures in Bathers at Asnierères are stripped or lightly clothed, and they lounge. From this contrast with the figures on the little boat in their different little world we can see that the foreground figures are probably poorer, of another class. And finally, if you haven’t seen it up beyond the little boats, the dim background soaks into view and you see what it is that limits the world of these bathers: a bridges, a line of industrial buildings and factory chimneys, that connect the two banks and literally form the painting’s horizon. That horizon runs at head height of several of the figures, right through the headspace of the large central figure. Certainly, a sense of psychological boundary is implied. That central figure himself looks thoughtful, affectless and dull; he is distanced from the viewer: his face is in shadow, his eyes cannot be seen. Above this horizon line, one chimney spews grey smoke up into the lively blue air.

The factory, then, labour, industry, smoke, constitutes the background of this world and structures this experience. The leisure time on display is then time off during which the prospect of the return to work glowers in the distance. The bathers take their rest within a new regime of time, standardised over large geographical areas not very long before this picture was painted, synchronisation spreading with the rail system. They rest, they swim or soak, between factory sirens or the whistles of the guards on the trains that brought them to this place and will take them away again.

Bathers at Asnières was Seurat’s first large scale painting to be exhibited, at the Salon des Indépendents in 1884. He had not yet developed his full pointillist technique of assembled dots of colour but the painting is nevertheless executed with marks small enough that what is often said of pointillism – that it abolishes expressive mark making and replaces it with an objective rendering of visual experience – holds true here. The Titian tradition that flows through Rubens, Rembrandt, Constable, Courbet, Corot and so many others, realised the presence, personality and emotional state of the artist in the handling of paint, the weight, speed and size of brushmarks. Here that tradition ends. The artist observes, calculates, composes, and draws back in order to see. His marks record not the feeling in his body as he responds to what he sees and strives to render it on the canvas but the millionfold pieces of information that hit his eyes. It is a technique that disclaims the importance of the heroic individual artist. It is anti-Romantic. It takes the side of the world against the individual, and it is ideal for realising the new reality that Seurat could see.

The smoke from the factory chimney is dark, concentrated where it first rises. Forming a cloud, it spreads to the right and catches the sunlight or chemically separates in some way so that an area of dingy yellow shows at its centre. Where it thins out, the edges of this plume of pollution are hard to discern. The small marks blur into a surround of similar small marks representing air. The two cannot be separated. Those carbon particulates might be anywhere in the air. Seurat has produced an image of what we are now calling the anthropocene, a world so conditioned and permeated by the human presence, particularly the human burning of fossil fuels, that evidence of it can be found anywhere in our environment. Bathers at Asnières appeared about eighty years into this altered world. The factories, multiplying, incessant, have been sending their smoke into the sky all the time since. It is impossible now for a reasonably alert individual to relax by a river without making a calculation as to how polluted it is and there are few urban rivers anyone would swim in at all. And, in a place as far from human hands as can be located on the planet, at a depth of seven kilometres in the ocean, in conditions of permanent darkness, shrimps guts have been found to contain plastic microfibers that they have swallowed. Those floating dots of pollution have drifted everywhere and all our vacations take place with smoking chimneys in the background, whether visible or not.

Perhaps all this seems simple and obvious. We know this is the constant background of our lives, striking ever more violently into the foreground with heatwaves and fires, floods, polar vortexes. I remember as a child having a leaflet produced by Greenpeace that warned about the dangers of deforestation in the Amazon and elsewhere. Increases in carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, it explained, would cause global warming due to the greenhouse effect. This was illustrated in a diagram by large red arrows of heat rising from the earth, bending back in the upper atmosphere, and returning down to where we are. I can remember the paper it was printed on, the light at the kitchen table where I read it, the dark outside the windows filled with more moths and nocturnal life than it would be today. That night was more than thirty years ago, and not for one intervening second have the chainsaws ceased or the factory chimneys stopped smoking. Obvious. We know this and have known for a long time. I write this during the burning summer of yet another hottest year on record. But mostly we look away. The figures in Bathers at Asnières’s show us images of our own anxious inaction or disconnected inwardness.

And behind them, we see the ghost of our present rising towards us as smoke that vanishes into everything, is everywhere.

So far I have been writing about Bathers At Asnières from memory and reproductions in books and on my laptop screen but the other day for the first time in months I stood in front of it again. The painting has been moved a little way from its usual wall and hangs as part of an exhibition of Samuel Courtauld’s collection of mostly Impressionist works, usually dispersed between the National Gallery, The Courtauld Collection and elsewhere. Reunited, glowing brightly in excellent lighting, these paintings convey the rush of Samuel Courtauld’s pleasure. Entering these rooms, I felt the surge of his enthusiasm. In that mood, the scale, the brilliance of Seurat’s achievement was immediately striking. The impact of the Bathers was first of all to do with its size – it is a large painting, a vista, a world you feel you could walk right into – and lightness. Set against a darker wall than usual, its airy summer blue hovers towards you, a great liberation of light. The figures in all that light are life sized, at least they seem so to me. Combined with the mostly static postures and the marmoreal, pale skin of the unclothed figures, carved out in three dimensions by contrasting outlines of darker paint, the connection to classical sculpture is evident. It is also pointed: the lack of ancient heroic poise, of self-possessed beauty, is the modern state. Perhaps Seurat is painting against hid contemporary Puvis de Chavannes, whose dreamy costume drama neo-classicism takes place in imaginary worlds, vaporous, nostalgic and unavailing when set against Seurat’s tenacious recording of what is actually out there.

The transition from a small to a movie screen is familiar to anyone who likes repertory cinema. The transformation is always most strikingly the increase of depth of field. It turns out that there was more of the world there already captured than you could previously see. In his outdoor paintings, Seurat is always interested in space, in the stiff, steady way that the world extends away from the viewer. This marks a difference from the Impressionists for whom space is typically one aspect of the shimmering intimacy of subjective experience. The Impressionists drape distance in among the perceptions of the viewer. Seurat preserves distance apart from the viewer’s experience, holds the objective world open such that it might be entered and traversed, which is to say that space in Seurat’s paintings makes concrete what the viewer does not yet know. Distance is a kind of question. In front of the painting again, I’m struck by how the people along the riverbank are distributed as they are on a warm day in a city park when, walking, you approach and pass, approach and pass, in a come and go of potential encounters. Space opens up within the group of buildings on the horizon. Their distinct standing is evident. I can see how it might be possible to walk around them, how you might have to approach them to enter for work. A plume of steam is visible low along the bridge, and I can infer a train travelling right to left. A line of Philip Larkin comes to mind:

And dark towns heap up on the horizon.

None of this cares for us.

The paradox perceived by both Seurat and Larkin: a world filled more and more with human structures, human designs, seems less and less human and engenders, in fact, loneliness, a sharp sense of the failure of connection where it really ought to be.

Three other paintings by Seurat formerly owned by Samuel Courtauld hang in this exhibition on the wall at a right angle to the Bathers. Two of them are outdoor views, The Bridge at Corbevoie and The Channel at Gravelines. Smaller, more like studies certainly than salon paintings, they too unfold deep spaces that I feel pulled to look into through their rectangular frames and the coloured edging that Seurat gave to later pictures that emphasise the polarity of flatness and depth. There are figures in both paintings but they are set much further back than in the Bathers, the closest of them in the middle distance. The figures in The Channel at Gravelines took me a long time to see at all. Their appearance arrived with the shock of how few tiny dots of pigment can manifest live people walking. The figures in The Bridge At Corbevoie are ranged along a riverbank on the left of the picture, much as they are in the Bathers, only they are all dressed and standing. The nearest of them is a child, neatly clothed, contained, quiet, in profile, contemplating something. I found myself unexpectedly moved by these figures, by my urge towards them, to reach out and make contact, pitted against the pictures’ resistance to the impulse. The paintings’ withholding of the figures, the scrupulous way in which they are both sharply defined and anonymous at this distance, creates a kind of quiet urgency, as though the painting knows something, some secret, that is refuses to or cannot communicate. In their reticence, the paintings call across to the viewer. There is something they want to tell me. The figures are distant in a double sense, both physically and as in the figure of speech “he seemed distant.” I realise that the figures in the Bathers, large and close and palpable as they are, are also distant, their moods, their thoughts unknown. Distance is a question. Seurat’s paintings hold all this distance open. What is actually in the world? What don’t I know yet? The Bathers At Asnières makes a great deal evident, much of it now unbearable, but it also keeps its distance. It is usual when writing about ecological breakdown to raise at the end some call to action, to offer some hope. I don’t feel that. In fact, I feel a great tiring wave of hopelessness as I satnd in front of the Bathers and it all comes back to me. But in Seurat’s painting there is at least the question of distance, the way the world holds itself away from us and continuously opens. It isn’t much to hold onto but it might be enough, enough for a little while anyway.

The Green Leaves At Night

This is in part by way of a bookmark. I want to come back to Stevie Smith and why she’s one of the poets I’m often drawn back to. There is of course something irreducible in the oddity, something particular that can’t be found elsewhere. There is the frankness and the whimsicality, the honesty about great pain delivered straight of in sing-along forms and jokes. Eccentric argumentativeness, moments of rapture, and of course the rending pathos of ‘Not Waving but Drowning’ and ‘I Remember.’ That way she has of launching a single singing line, (as at the end of ‘I Remember,’) that goes on out of the poem, as it were, alone, in flight through your mind forever - something that Denise Riley can do too.

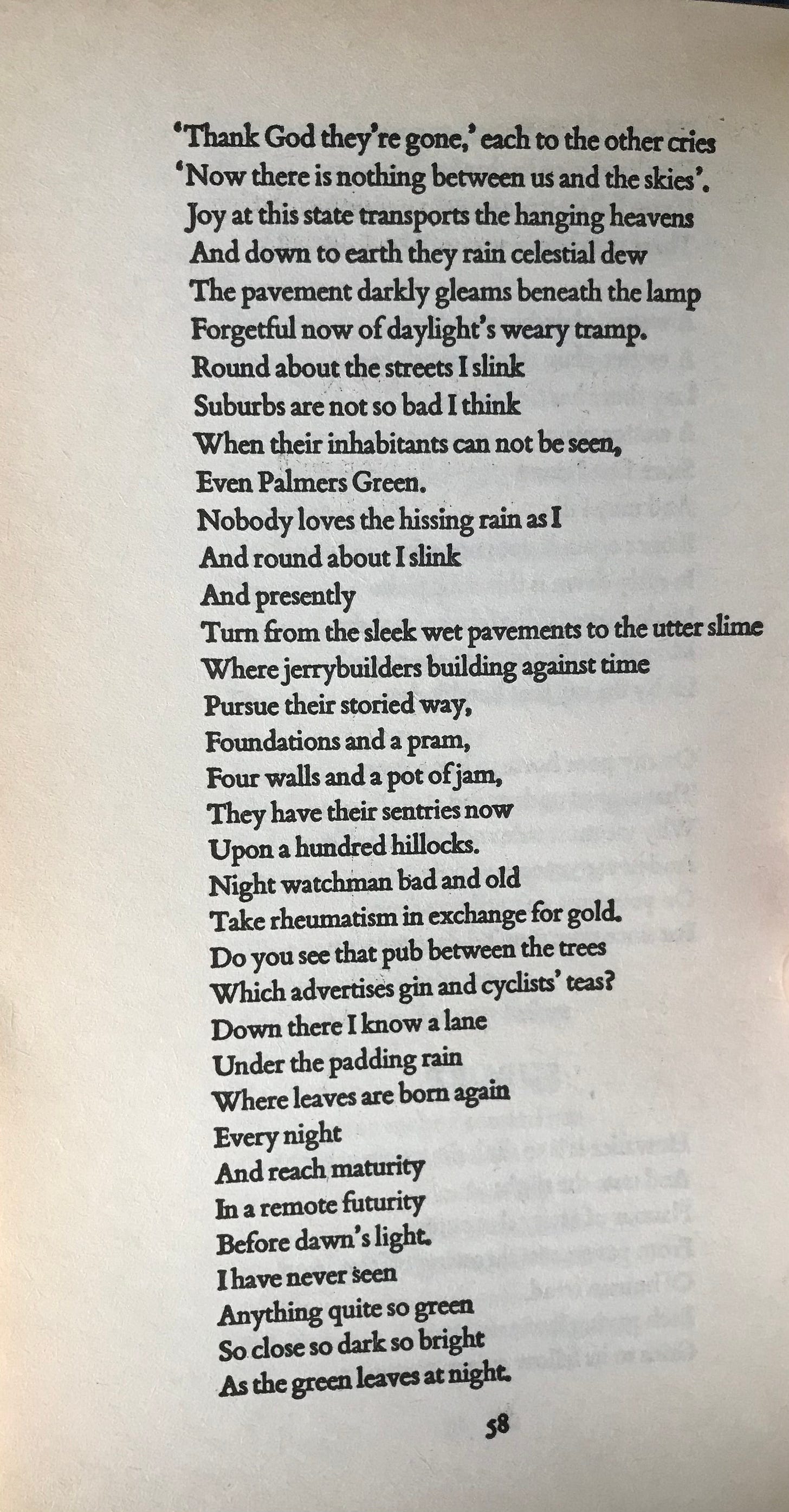

Plath loved her poems, Larkin too. Here’s one I like for the familiarity of London suburbia and the hushed, charged moment towards the end of ‘I have never seen / Anything quite so green / So close so dark so bright / As the green leaves at night’ that gets me every time. It’s not available online so I’ve taken photos:

Youtube Treasure #4

This is another bookmark. I want to write more about photographer Alec Soth’s vlogs and the subject of photos and photo books in the future. I recently discovered that the photographer Alec Soth (Soth pronounced, as he insists, to rhyme with ‘both,’ not ‘moth’) had started sharing talks and ideas on a Youtube channel during lockdown. There’s a lot of wonderfully rich engagement in them and many suggestive ideas about narrative and the creative process. This is the first of those videos that I came across, as good a place to start as any.

Weather Diary

January 26th

0 degrees. The morning after the day before. Broken cloud. Light breeze. People clearing channels down their paths and along the pavement with snow shovels. People tending to their cars, brushing the snow out of their eyes.

January 27th

-1 degree. Cold morning of clouds and sun and wind. Brisk shine. Colourful shapes. Leaps of airy blue between the clouds. Then, in the afternoon, clouds increase and merge: closed in a white room.

January 28th

O degrees. Brittle, bone-white light. Smashed glass of fallen icicles that fell in the night, clear and sharp.

January 29th

1 degree. Snow, falling vertically, quietly, without wind. Thick, heavy, soft, like a sweater pulled down over the head. And then we’re through. In the afternoon the only snow that falls is scuffed off of oak branches by squirrels as they run along

January 30th

-2 degrees. Overcast. A Monday. The grey of subway cars, of a working day.

January 31st

-7 degrees. The sky clear. A new, revelatory cold. Realizing the planetary surface, open to emptiness, as though one could almost look through the pale blue miles of atmosphere into space beyond. Down here, the snow is very bright. Struck by the low-angled sun its crystals blaze.

February 1st

-5 degrees. Delicate sky. Scrims of fine cloud in the blue. Face-numbing cold. A tall fir tree, clustered with pinecones towards the top, contains a bird out of sight, either a dark-eyed junco or an American goldfinch, I think. A scratchy, scrambled continuous song, a broadcast that seemed to be emitted by the tree itself. For other living creatures and not for me. Encrypted end to end.

February 2nd

2 degrees. Smooth, wide clouds, dove grey. In the evening, a new violence. The temperature dropping, trees surging in the wind. The day roughly handled, hurried roughly into night.

February 3rd

-18 degrees. Air stings the lungs, a piercing emptiness. Houses issue bright steam from their outflow pipes. Car exhaust turns to vapour. The wind hurts; it rattles the trees. The sun floods everything with light but no heat, a distant radiation. Canadian teenagers don’t care though, walking to school in sweatpants and light jackets, heads bare, interested only in each other.